As you may or may not have heard, Chili John’s in Burbank is struggling. As per an LA Times story last week, they’ve been subsisting on barely $200 a day. With that kind of revenue, ownership said they would have to close within a month. But although COVID-19, the Writer’s Strike, the fires, and the general downward turn in the entertainment industry have all dealt a mighty blow to LA small businesses, especially in studio-adjacent Burbank, Chili John’s fans are legion, including a few famous faces like Patton Oswalt and Andy Richter who’ve come out of the woodwork to support the old diner. It is, thankfully, once again a place where you will likely have to wait for a seat, anxiously standing behind those already seated much like at The Apple Pan. Hopefully this kind of business is sustainable so Chili John’s can keep making its famous century-old chili recipe.

But over the course of the last week or so, I’ve seen a troublingly common sentiment about the place. Many young, modern “foodie” types are actively disdainful of Chili John’s. I got quite a few comments online along the lines of “good riddance” or “I’m glad it’s closing,” “it’s an eyesore,” “the service is terrible,” etc. This came as something of a shock to me. Have these people never heard of a dive before? They’re not supposed to be cute, and you shouldn’t expect people to bend over backwards for every Karen that walks through the door. These people simply don’t understand, if you ask me.

And of course there’s the chili itself. It’s not like other chili in town - rather than ground beef or big chunks of beef, its more of a ragu that’s been broken down into fine particles after 20 hours of long simmering. Its spiciness is unique, with strong notes of garlic, black pepper, and cumin; reminiscent of the Southwest, but not exactly in the way people these days are used to. You can adjust your spice level, of course, and although I find the chili to be flavorful enough on its own, it’s not so powerful that it can’t serve as a perfect base for a wide variety of toppings. At Chili John’s, you can modify your chili’s flavor and texture by adding cheese, onions, sour cream, oyster crackers, hot sauce, pepperoncinis, apple cider vinegar, or even “bean juice.” And of course there’s that thick layer of grease that accompanies every bowl as Chili John’s true calling card. They didn’t forget to skim it, it’s there on purpose—pure beef tallow that has absorbed the spices of the cook. It’s where all the flavor is, and it’s an approach to chili that is very old-school.

So allow me, reader, to thoroughly explain the significance and the greatness of Chili John’s and its famous chili in order to silence any detractors. But in order to articulate my apologia, we’re going to have to delve a bit into the history of chili in America.

…

Chili is an all-American kind of dish, adaptable to nearly any locale and loved by many with a flair for unpretentious fare, though it is of course most strongly associated with its home state of Texas. There are many prehistoric strands that converge upon what is now known as chili: supposedly the Aztecs were eating thick stews seasoned with chili peppers in pre-Columbian times, though beef was not introduced to the mix until the Spanish started cattle ranching in Mexico. This early chili though was more similar to what we now know as mole poblano.

Chili as we know it began to take shape in the 18th and 19th centuries. Rancheros in Mexico (which at the time included the states of the American Southwest) dried and preserved beef in the form of tasajo, which is still popular in Mexico, but is also a historical predecessor to beef jerky. Unlike jerky, which in the US is usually eaten by itself, tasajo is often rehydrated by adding it to a stew. It was these tasajo-based stews, called carne con chili, that formed the foundation of what would become modern chili.

Chili became popular cowboy fare in the mid-1800s, enjoyed by ranchers and miners on the trail. This early chili was rough, simplistic: essentially just beef stew with chili powder and fat. These ingredients were preserved as dried chili blocks, which were transported over long distances in harsh conditions, to be rehydrated as a stew around a campfire. For similar reasons that it became popular on the range, chili would have a long history of popularity among prison inmates that extends well into the 20th century.

In the 1880s, Tejano and Mexican women started setting up stands in downtown San Antonio, where they developed what is now known as chili con carne. The so-called “chili queens” became a staple of San Antonio, even becoming a minor tourist attraction. Capitalize on the notoriety of the chili queens, the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair featured the San Antonio Chili Stand, which spread the gospel of chili to the rest of the world. It would be thanks, at least in part, to this exhibition that chili began to move beyond its Texas origins. But the chili queens enjoyed popularity in San Antonio until 1939, when the state cracked down on sanitation at the chili stands. By 1940, most of the chili stands were gone, to be replaced during and after WWII with chili parlors, which could be found from Oklahoma to Wisconsin and California. And that’s where Chili John’s enters the story.

…

There are many different forms of chili to be found in America, with many bearing rather little resemblance to the Texas-style beef stew seasoned with chili peppers that they call chili down in the Southwest. How do we get from the chili queens to, for example, the slightly sweet, cinnamon-flavored Cincinatti variety? Or to white chili, or Yankee chili for that matter?

In the early 20th century, especially around the Depression era, there were many nascent budget meals beginning to formalize around the country. For example, an item known as “loosemeat” began to rise in popularity in the Midwest during the 1930s, and is still something of a specialty in Iowa, where it is sold by the Maid-Rite restaurant chain. Around the same time, chili parlors began creeping northward from Texas, and a wave of Greek immigration saw many Greek restaurateurs trying their hand at local cuisine, approaching it with their own sensbility. I think some confluence of these influences led to the rise, for example, of Cincinatti chili. Being budget meals, these various chili-adjacent dishes did not command the respect of the media or high society, so their histories and various transformations are generally poorly documented. But I think a number of similar dishes that were popularized around the same time as chili just got lumped into the chili label, resulting in many, sometimes far-flung mutations. Cincinatti chili might not be chili under an 1890 definition of the dish, but by 1940, what was commonly understood as chili likely would have included this variation.

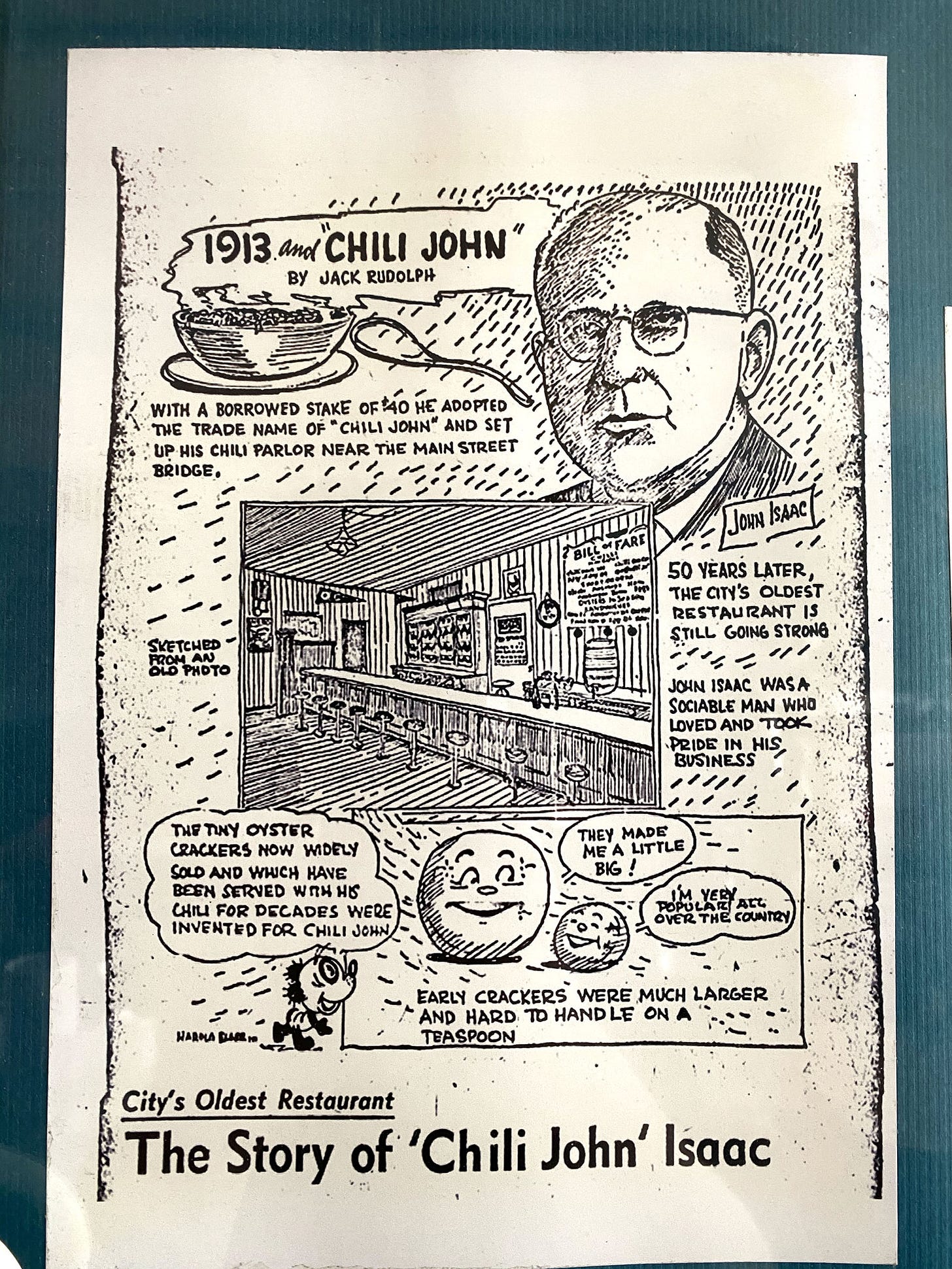

John Isaac, a Lithuanian immigrant to Wisconsin, would later be known as Chili John himself. At some point around 1900, he owned a bar in Auburn, Illinois. At some point he became a certified chili fan, and somehow acquired a recipe he served at his bar. Over the years he would experiment with this recipe, adding his own unique touches. By 1913, Isaac decamped to Green Bay, where he would found the first Chili John’s. This chili was often served atop spaghetti, accompanied by oyster crackers developed specifically for Chili John’s. In 1946, Isaac’s son would move to California and found the Burbank Chili John’s, which is now the last remaining location.

Now the reason I gave that whole spiel about the history of chili was to say that Chili John’s chili preserves an incredibly old, archaic form of chili. Allegedly gestating since 1900, this chili recipe comes very close to what the chili queens of San Antonio were probably serving. And that’s important, because even in Texas, the chili parlor is a dying tradition, and none that do exist can claim direct continuity to the chili queens, most of them having started during the chili revival of the 1960s and 70s, such as Tolbert’s in Grapevine or the Texas Chili Parlor in Austin. Other chili parlors, such as Ike’s in Tulsa, OK, serve a gloopy sauce of ground beef that resemble what you’d find on a Coney dog.

Chili John’s represents something a little different, and a good deal older. It’s not based around ground beef, but it also doesn’t feature big chunks like a contemporary Texas bowl o’ red. The ingredients rather are pulverized and disintegrated, which speak of the long hours of cooking that the chili is subject to. Their dogged commitment to using beef tallow approximates the effect of beef suet—kidney fat, which was probably the most common cooking fat in the Old West. The way it congeals at the top, intended as something of a seal of quality, is just so old world to me. That grease would turn stomachs among serious foodie types today, but made my dad and my grandpa’s mouths water. It’s history in a bowl.

And of course, beyond the chili itself, the chili parlor, whether it’s in Texas or Illinois or California, similarly represents some of those old world values. How many other foods are so important that they get their own parlor? Chili should be proud to stand among the ranks of pizza and ice cream as parlor-worthy foods.

…

I think the young folks of today are losing their appreciation for the dive joint. A dive is a place that’s a little rough around the edges; there might be flies on the windowsill, some unswept dust in the corner. The service may leave a little something to be desired. Whoever’s behind the counter probably won’t win any awards for couresy or etiquette. You get the idea. And what arrives on a plate in front of you may be greasy and lacking that photogenic quality. But in the best of cases, you make it past these hazing rituals in order to enjoy something truly outstanding. The best dives take an unassuming, inexpensive, and perhaps even mildly off-putting dish, and through some alchemical process, make it into something transcendent that rivals the finest chefs in the land.

People who appreciate dives understand that all the things that would make any other restaurant bad, are intended here as tests of mettle. Your willingness to make it past the modest environs, challenging service, and inevitable indigestion proves to the world that you have earned the right to damn good food at a fair price. You have searched high and low and, in the unlikeliest of places, you have found manna from heaven, and can from now on serve as the shepherd of culinary delights to your most favored friends. Now not all chili parlors are necessarily dives, but many are, and proudly so. Chili John’s certainly falls into this camp, which is why many seem to turn their noses up at the place

Newcomers don’t always understand the dive dynamic, though. Yuppies get the stinkeye from the cook and they start clutching their pearls. But we begrudgingly have to admit that, in this economy, we might need the yuppies. If Chili John’s traditional clientele isn’t enough to sustain it, then I admit we may need to do some outreach. So please, yuppies, don’t be offended. It’s not that they don’t like you. That’s just how they do things around here. But have a little patience, a somewhat open mind, and moderately thick skin, and you might just enjoy yourself. Talk to the people next to you. It’s a diner counter, it’s meant to facilitate equality and decent conversation. Get to know the kinds of people who come here. And please, enjoy the grease.

Having lunch at Cilli Johns today. Not a spare seat at the counter. The staff is scrambling. Will the next gathering be here?