Traditionally speaking, New York isn't really a burger town, it's a hot dog town. Sure, there are notable burgers in New York, from Paul's Da Burger Joint to JG Melon's to the more recent smashburger trend. But smashburgers were actually invented in the Midwest, New York just happened to be the focal point of a particular moment in the food trend cycle. And as for the older places, they can be good, even great, but they don't constitute a particular style that is unique to New York. Not in the way that Ohio, Oklahoma, and Southern California all have multiple, regionally distinct and historic burger styles. But New York has all those places beat when it comes to hot dogs, and this not only because there is a particular way that New Yorkers like their hot dogs, but because there is almost an entire subculture surrounding New York dogs.

Why, historically, does a place like New York remain a hot dog holdout from olden times, while other places come to be known far more for burgers? I'll admit that the reason could be entirely arbitrary, but let's entertain, for a moment, the possibility that these preferences reveal something about the character of these places.

Through the majority of the 20th century, there were at least three main hot dog styles (Eater identifies several more that can be found, but I will be focusing on those styles that truly originated in NYC): the pushcart hot dog, the kosher deli hot dog, and the papaya-style hot dog. The pushcart dogs, almost universally of the Sabrett variety, are steamed in water, kept warm as they're sold throughout the day. These are hot dogs of desperation, enjoyed for convenience and bare sustenance more than any abiding love of the things. All-beef kosher deli dogs tend to be of unorthodox proporotions - either slightly longer or slightly girthier than the norm - and have just a bit more garlic and spice compared to a pushcart hot dog, perhaps an echo of the salami that kosher delis all used to hang from the windows in the old days. And then there's the papaya-style dog, which is a Marathon-brand beef frank griddled to a slight char, traditionally served with papaya juice (to be fair, Katz’s dogs are also Marathon brand, but spiced to their specifications). All of these together comprise variations of the New York-style hot dog, always topped with sauerkraut, mustard, and in its more casual contexts, a tangy onion sauce.

And of course, there's Nathan's, which is in a category unto itself and was a key player in the very earliest days of America's infatuation with wieners. In a way, they are the perfect industrial meat product, but in its perfection I find them uninteresting, inoffensive. It's a fantastic place to stop once or twice a year when you swallow your pride and go to Coney Island, with its fantastic display of vintage neon and open air ordering stations. But apart from that Coney Island cachet, I feel it doesn't contribute all that much to the conversation about New York hot dog culture. It does host the National Hot Dog Eating Championships, which is undeniably awesome, but there's a reason for that - it is the hot dog to be eaten by the dozen, not savored by the one or two.

But this review is about Gray's Papaya, so let's get to the point already. Gray's is originally a spinoff of Papaya King. They're the original papaya dog (not to be confused with Papaya Dog), founded way back in 1932 by Greek immigrant Gus Poulos. The papaya juice actually came first; sort of a prehistoric health food kick perhaps. Then it became the juice place that also sold hot dogs. Over time it became the hot dog place that also sold juice. It would spawn countless imitators, and also make several attempts at expanding to other locations both in New York and across the country, but none of those offshoots lasted longer than a couple years at a time.

Gray's Papaya started out as one of these ill-fated attempts at expansion. Perhaps sensing the inevitable demise of his little slice of the hot dog world that seems to follow Papaya King franchisees, Nicholas Gray shut down, regrouped, and reopened in 1973 as Gray's Papaya.

Obviously, Papaya King is the older of two; respect where respect is due. But I have always been a bigger fan of Gray's Papaya. Truth be told, their dogs are virtually identical. Supposedly they have proprietary recipes for this and that, but really, they are basically equivalent. Which one is best is conpletely subjective. I like to think that Gray's griddles their hot dogs a little longer, but I admit there's no real proof of that.

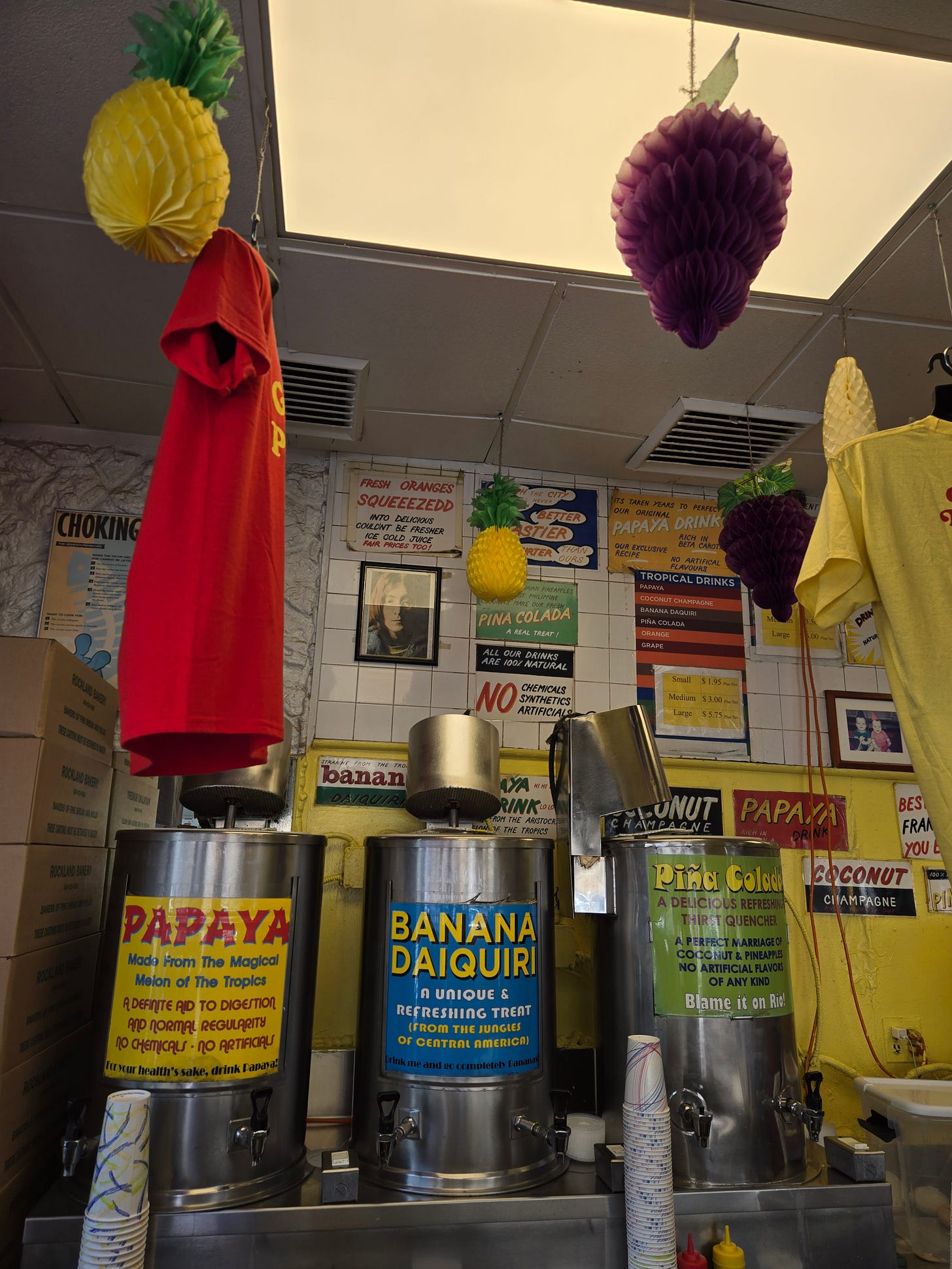

But there are a couple of legitimate reasons to prefer Gray's. For one, Papaya King recently had to move from their original location, and has lost a good deal of its old-school charm. Gray's, on the other hand, retains the funky, ad hoc appearance that both places were long known for. Gray's is also known for the Recession Special - New York's most economical meal. Currently priced somewhere around $7, it includes two hot dogs and a drink. It may not look like much, but it hits damn hard when you're hungry and broke (although it’s not as good a deal as it once was - the recession has even hit the Recession Special).

It's worth mentioning once again that Gray's and the King are far from the only papaya-style dogs out there. Over the years there have been dozens of dirt cheap fast food stands specializing in the conspicuous combination of hot dogs and tropical fruit juice. A few still carry on, like Chelsea Papaya and Papaya Dog, who thankfully serve the downtown crowd, though they don't quite measure up to the elder statesmen uptown.

The hot dogs at Gray’s themselves have an undeniable appeal. They're long and thin, quite firm with noticeable tones of garlic. The griddle not only lends these dogs a very slight crunch on top of the usual snap, but also sizzles the fat and imparts a slight, savory greasiness. They curve slightly at the ends, too, resembling a smile on a bun. As mentiond earlier, the three acceptable toppings are mustard, sauerkraut, and onion sauce. The onion sauce is ketchup-based, zesty and tangy. I love sour flavors, but I have to admit that all three of these together can overhwelm the taste buds. I recommend mustard on both dogs, add kraut to one, onion sauce to the other, and switch off taking bites of either one.

The papaya juice does help cut through the briny sourness, though. It's a whipped drink, rather viscous and sweet. There are other flavors like pineapple, but I've only had the papaya. And maybe under other circumstances I might find this intolerably, cloyingly sweet, but it's an excellent counterpoint to the pungence of the hot dogs. It's all cheap eats to be sure, but satisfying and remarkably robust. You can enjoy it all standing up at one of the counters along the wall of Gray's Papaya, where you can appreciate the colorful, eclectic decorations and signage accumulated over many years. It all gives the place a feeling like it's an ever-evolving, yet palpably old and historic kind of thing.

So what does all this say about the culture and people of New York? The wiener itself, plus the mustard and sauerkraut, bely the frank's German-Jewish origins. The onion sauce, meanwhile, is purely a product of industrial society, developed by a food scientist specifically for Papaya King and therefore lacking any heartwarming origin story of ingenious pluck or serendipity. The papaya juice adds a certain kaleidoscopic element, an odd but oddly fitting complement, a testament to the ability of the city to bring two seemingly unlike things into proximity to startling, impressive results. Optimized for convenience and thrift, it is unpretentious and accessible, but at the same time uncompromising - just try to endure the withering looks of those around you if you try getting a dog with just ketchup.

They're also a highly modular foodstuff. With hamburgers, you know you're settling into something like a full meal. But with hot dogs, it's like: do you just want a quick snack? Just get one. A little hungrier? Get two and a papaya juice. Absolutely famished? You can get three or four pretty tasty wieners without breaking the bank. Also, with hamburgers, the toppings are generally less important than the substantiality of the beef patty. When it comes to hot dogs on the other hand, the toppings are all-important. So much can be revealed about a personality via their hot dog toppings. Ketchup eaters are childish and impetuous; mustard-only means you're a real straight shooter. Onion sauce is for the hedonists, the thrill seekers, those who like to live dangerously. The same just doesn't seem quite true about burgers and their toppings, which tend to be less diverse.

In a certain way, hot dogs seem a little less commercial, too. There are, after all, many well-known national and regional burger chains. Even New York, for many years lacking their own successful burger chain, can now lay claim to Shake Shack. But aside from Wienerschnitzel, there are very few chains specializing in hot dogs. Most hot dog specialists, in New York or elsewhere, are one-off, mom-and-pop affairs rather than corporate juggernauts. Maybe this is because hot dogs are inherently kind of unspecial. A talented fry cook can elevate a burger to something almost transcendent, but for the most part, a hot dog is a hot dog is a hot dog. They almost all come out of a factory, one of identical thousands. But that doesn't stop people from wanting them, so enterprising individuals arise to fill the demand. And sometimes, the gimmicks they adopt to stand out from the crowd become loveable quirks, artifacts that do in fact make them unique. It's those quirks, like the papaya juice or the neat little slogans or the hand-drawn signs taped to the walls, plus all the various imitators that put their own spin on things, that really show the soul of New York. And for that I say, all hail the papaya.